Inclusion Targets: What's Legal?

INCLUSION TARGETS:WHAT’S LEGAL?

Recruitment, Hiring, and Promotion

As the entertainment industry reckons with the glaring absence of diversity in front of and behind the camera — along all metrics, including race, gender, disability, LGBTQ status — so many leaders want to do better. After all, it's not just the right thing to do — it also yields a better product.

But can a company try to fix those imbalances by taking identity characteristics into account when making employment decisions? Can it go one step further and set numerical diversity goals? The answers to both are YES — if done properly. Here’s how.

Inclusion goals (a/k/a targets) are legal, accepted tools for combating underrepresentation.

The law grants private companies latitude in taking race, gender, and other protected traits into account. Congress and the Supreme Court have acknowledged “the value of voluntary efforts to further the objectives” of anti-discrimination statutes. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity (EEOC) also endorses affirmative inclusion efforts, including numerical goals, if they are consistent with the law.

What does “consistent with the law” mean?

- The inclusion effort seeks to remedy a protected group’s low numbers in a certain job or sector and the disparity results from past barriers to opportunity — in the larger workforce, or in your company.

- “Low numbers” means a gross imbalance between the percentage of protected group members in a particular job as compared to their percentage in the relevant labor pool.

- The program establishes numerical goals or targets (such as “aim to double the percentage of women we hire to direct television shows with our studio this season” or “we will hire crews that better reflect the demographics of California’s skilled labor pool”) but not rigid quotas or set-asides (such as “the next 5 people we hire in X job must be women” or “we need 10 Black people in Y job”).

- The goals are achieved through measures tailored to fix the specific barrier(s) identified.

- The program does not unduly harm members of non-targeted groups, such as by refusing to hire any people from those groups, or firing such individuals in order to reach the numerical target.

- The individuals who benefit from the program must be qualified for the jobs in question.

- The program is temporary; once the goal is attained, it cannot be used to maintain those numbers. Short-term timetables help monitor progress toward the long-term goal.

- The program is reviewed regularly to assure that the goals and timetables are still justified, and to assure that non-targeted groups are not being unduly harmed.

Examples of inclusive hiring goals or targets found to be “consistent with the law”

- A county agency’s long-term goal of achieving a percentage of women employed in historically maledominated jobs that matched their percentage in the local labor force, with short-term goals of “a statistically measurable yearly improvement in hiring, training, and promotion of” women.

- A steel manufacturer’s practice of reserving 50% of spots in a training program for Black workers, until Black workers’ representation at the plant matched their percentage in the local labor force.

- A California city government’s plan to hire and promote women and people of color in greater proportions than their numbers in the city population, until their numbers in the government matched their percentage in the local labor force.

There are recognized “best practices” to help inclusion programs achieve results.

- The best solutions come from understanding why a company has a problem in the first place. Identify the barrier(s) that have created diversity imbalances. These may vary from job to job.

- Solutions are needed to each barrier at different points in the pipeline — hiring versus training and promoting versus environmental factors that drive certain groups out once hired.

- An outside evaluator should do this preliminary analysis; it assures proper methodology.

- Numerical targets should be keyed to the number and kind of opportunities expected to be available, and the availability of qualified (or qualifiable) applicants.

- Management must communicate about the program and its goals, make clear that unlawful discrimination will not be tolerated, and monitor its effectiveness.

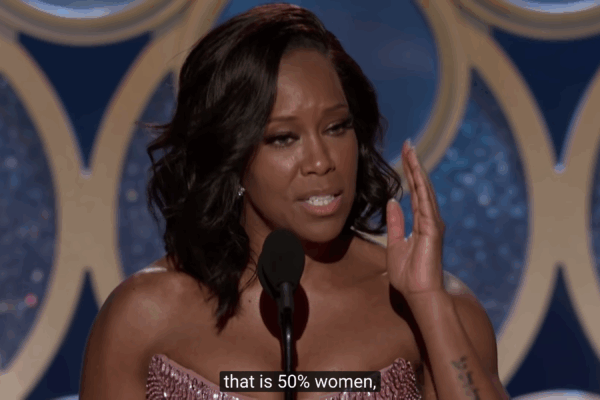

Is the “inclusion rider” consistent with the law? YES.

- The rider idea was inspired by the “Rooney Rule,” which the National Football League has used since 2003 to require that at least one person of color is interviewed whenever a team fills a head coach job. (Employers in the tech and legal sectors have since adopted their version of the Rule.)

- The rider, created by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, the law firm of Cohen Milstein, and Pearl Street Films, is a provision included in the contract of an actor, director, or writer.

- The provision requires inclusion of women and other underrepresented groups at the interview and casting stages, and demands “affirmative efforts” to hire those individuals.

- The rider passes legal muster because its numerical mandate diversifies the candidate pool rather than create a permanent set-aside job, it demands that all candidates be qualified, and when it comes to hiring, it uses aspirational language like “affirmatively seek” and “all reasonable efforts.”

Related Content