When relatives arrived to help Tyisha Miller with a flat tire, they found her comatose in her car, doors locked, and a pistol on her lap. After failed attempts to arouse her, they called 911 emergency.

The four officers who responded broke a side window to open a car door, startling Miller, 19, who had the gun for protection. When she reached for it, the officers opened fire with a barrage of 24 shots into the car, four to her head.

Miller’s death in 1998 generated outrage across the country, especially in African American communities. That three white officers and one Latino would gun down a young black woman under those circumstances accentuated questions about virulent racism in the Riverside, Calif. Police Department.

Even though Miller’s relatives had called police, they also had sent someone to retrieve a spare key to open the car door. Miller, of Rubidoux, Calif., an unincorporated area of Riverside County, would still be alive had only the officers waited for the key, her relatives maintained.

Miller’s death became such a high profile case that it helped serve as a catalyst for a local movement amongst Riverside residents asking for more accountability from their police department. The Riverside Coalition for Police Accountability was one group organized at that time.

Ultimately, the city established a civilian oversight agency called “The Community Police Review Commission,” and then-Attorney General Bill Lockyer also ordered Riverside Police to make changes as part of a consent decree.

But many local leaders in the Inland Empire, San Bernardino and Riverside counties, don’t feel like much has changed in how their communities are policed in the 16 years since Miller’s death. Surely, policing techniques have changed with the introduction of body cams and new training methods. But the Inland Empire remains a disturbing hotspot where police misconduct rarely, if ever, is corrected.

For that reason, the ACLU of Southern California is providing communities in Southern California with the tools they need to make sustainable reforms in police practices.

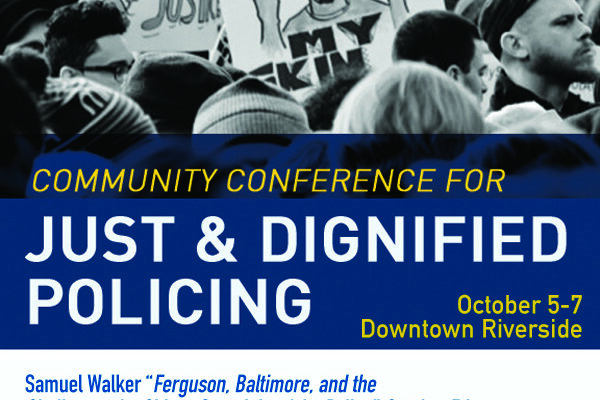

Alongside our partners from the Riverside Coalition for Police Accountability, we are co-hosting a free, three-day Community Conference in Downtown Riverside, October 5-7, to help provide individuals with legal and policy information involved in policing.

Make sure to RSVP online. We hope you can join us so that you too can be a part of the collective efforts to create transparency, accountability and justice for all communities.

California data on deaths in police custody between 2009 and 2014 compiled by the Attorney General’s office showed that the second deadliest city law enforcement agency in the state is the San Bernardino Police Department with 17 homicides for a force of 224 sworn officers.

Among counties, Riverside with a population of 2.3 million is second in the state with 63 deaths in custody, and San Bernardino with a population of 2 million is third.

Without the proper systems in place to address issues like the high number of deaths in custody, the public cannot hold any police agencies accountable.

Will anyone be held accountable for the death in custody of Dante Parker who San Bernardino sheriff's deputies Tased 23 times before he died?

The whole country saw the video of San Bernardino County Sheriff’s deputies pummeling Francis Pusok as he lay on the ground attempting to surrender. But there was some accountability in that case. Three of the 10 deputies involved in that beating have been charged with felony assault, and the county has paid Pusok $650,000.

A statewide ACLU poll released in August found that almost four in five likely California voters (79 percent) say that where police have engaged in misconduct, the public should have access to the findings and conclusions of investigations into that misconduct.

That overwhelming support for reform carries across all ethnicities within the state, including more than nine out of ten African American voters (91 percent), five out of six Latino and Asian voters (84 percent) and over three-quarters of white voters (76 percent).

California voters overwhelmingly see the absence of police transparency as a problem and support reforms that promote transparency. The law enforcement lobby has been the main obstacle to any reform, stopping every effort to bring transparency to police misconduct investigations. It is time for elected leaders to listen to the voters and embrace meaningful reform.

RSVP for the Riverside Community Conference for Just and Dignified Policing

Luis Nolasco is a community engagement and policy advocate in the Inland Empire office of the ACLU of Southern California.