Got an opinion about an issue in the OC? The Orange County Board of Supervisors wants you to keep it to yourself.

Democracy depends on the free flow of ideas, but the board -- one of the most powerful local government bodies -- has adopted rules strictly limiting the opportunity for the public to be heard at its meetings.

On Monday, we sent a letter to the supervisors, stating deep concern that their limits to public participation not only run counter to sound public policy, they also violate the state's Brown Act and the First Amendment.

Instead of the board acknowledging its role as servants of the people, it treats the community as an impediment to conducting its own business. It’s the duty of supervisors to listen to their community; it’s not an inconvenience to be endured, it's their job.

Our letter documented four main ways the board obstructs public input:

Time limits

Last year, the board reduced the amount of time a speaker could comment to three minutes -- for the entire meeting.

The time limit gets worse when numerous people sign up to speak. At one meeting, the board restricted comment to one minute per person, except, it seems, when the board liked what the speaker had to say. Thus, the manager of a company that offers a "VIP wine tour" was allowed to bust the time limit. Meanwhile, those at the meeting to talk about poverty and homelessness were brusquely cut off at the minute mark.

The Brown Act gives the public the right to attend and participate in local government meetings. Government code stemming from that act states that a "local agency may adopt reasonable regulations [...] limiting the total amount of time allocated for public testimony."

The key word is "reasonable." We believe the restrictions imposed by the board -- and the fact that those rules are unevenly applied -- are hardly reasonable.

Addressing a specific supervisor

The board also prohibits people from directly addressing individual supervisors. Comments must be directed to the “board as a whole through the chair.”

Preventing the public from addressing an individual supervisor directly leads to absurd results. It would prevent a person from responding to a remark made by a particular supervisor, ignores the fact that the supervisors are not a cohesive body and subverts the supervisors’ roles as representatives of specific districts.

Comment cards

The board requires speakers at meetings to fill out a request form, including the person's name. But under the Brown Act, as the League of California Cities says, "public speakers cannot be compelled to give their name or address as a condition of speaking."

Furthermore, the right to anonymous speech is guaranteed by the Constitution. As one decision put it, "The right to speak anonymously was of fundamental importance to the establishment of our Constitution."

As a practical matter, individuals might not come forward to speak if they fear disclosing their identity could lead to retaliation or harassment.

Signs

The board has a rule that bans signs, posters and banners that "could impair the safety of individuals in the event of an emergency." This is not unreasonable, except that the board and sheriff seem to interpret it as no signs at all.

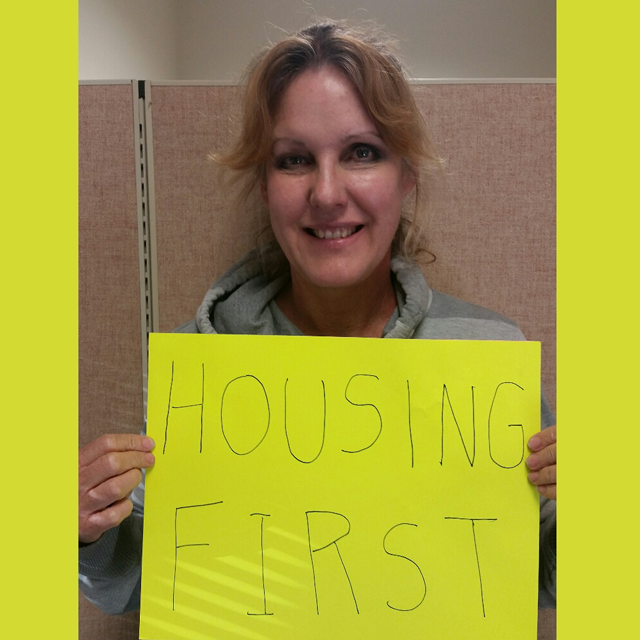

Eve Garrow, our homelessness policy analyst and advocate, took a sign to a recent meeting that said: "Housing First." The handwritten sign was not exactly a flashy bit of craftwork -- it was literally made from cardstock, about 11-inches by 14-inches.

The board has a rule that bans signs, posters and banners that "could impair the safety of individuals in the event of an emergency."

"The sign was so small and flimsy; it would not present a danger to anyone," Garrow said. Nonetheless, she was told she would have to leave it outside the boardroom.

Not only did banning this harmless sign go against the board's own rules, the use of non-disruptive signage clearly falls under First Amendment protections. And, given the board’s approach to public comment, at a large enough meeting, it could be the only way of communicating with the Supervisors.

It's clear to us that the O.C. Board of Supervisors must immediately begin the process of rescinding and replacing these illegal policies and practices, and fundamentally change its approach to the community it purports to serve.

Otherwise, the ACLU SoCal will be forced to consider legal steps. And our dissent will likely take longer than three minutes.