For the attorneys, organizers, and community members on the ground, the Kern County immigration raid was more than just a headline — it was a turning point in the fight to protect their neighbors from fear and injustice.

On January 7, 2025, residents of California’s Kern County woke to a startling sight: green-striped Customs and Border Patrol SUVs parked in places they had never been seen before. The SUVs were in small business parking lots and dotted along rural highways. By day’s end, the immigration enforcement raids had begun. More than 70 people were arrested and taken into Border Patrol custody.

In Kern County, immigration enforcement is typically handled by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Even then, arrests are usually targeted at specific individuals. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), on the other hand, rarely operates outside its 100-mile zone near the U.S.–Mexico border. Kern County is almost 300 miles away from that area. But on January 7th, Border Patrol agents cast a far wider net. They didn’t go after individual people. Instead, they stopped people of color, especially those who agents believed were farmworkers. Their tactics were aggressive and unprecedented.

For many, the raid — dubbed “Operation Return to Sender” — felt like more than a one-time sweep. It marked the start of a troubling new chapter in immigration enforcement.

“This Was Racial Profiling at Its Most Basic Level”

For Bree Bernwanger, senior staff attorney at the ACLU Foundation of Northern California, the morning of January 7th started just like any other: then the calls began. Reports flooded in from Kern County that immigration agents were spotted in strange places throughout the county.

“They were slashing tires, smashing car windows,” Bernwanger recalls. “They pulled over cars, they grabbed people in parking lots, and there really didn’t seem to have any reason to do it except that people were brown. This was racial profiling at its most basic level.”

At first, everyone assumed these agents were ICE officers. But late one night, as Bernwanger checked the government’s detainee locator, she saw something unexpected. The people that had been arrested during the raid were in CBP custody. Border Patrol, which typically operates near the U.S.-Mexico border, had driven 300 miles into the Central Valley for a massive raid.

Agents targeted predominantly Latine neighborhoods and worksites, detaining people indiscriminately. People abducted were taken to a makeshift processing site in Bakersfield, then bused to an “icebox” in El Centro — freezing, windowless rooms with no beds, limited food, and no access to lawyers. Border Patrol coerced many into signing “voluntary departure” forms, misleading them about the consequences, which could include a 10-year ban on reentry.

Roughly 40 people were summarily expelled to Mexico without a hearing. Others, including U.S. citizens and longtime green card holders, were released but left shaken. Families and communities now live with the aftermath — fear, separation, and the knowledge that, as Bernwanger put it: “Everyone subjected to it is now picking up the pieces.”

“These folks’ rights are being violated. This should be concerning for all of us.”

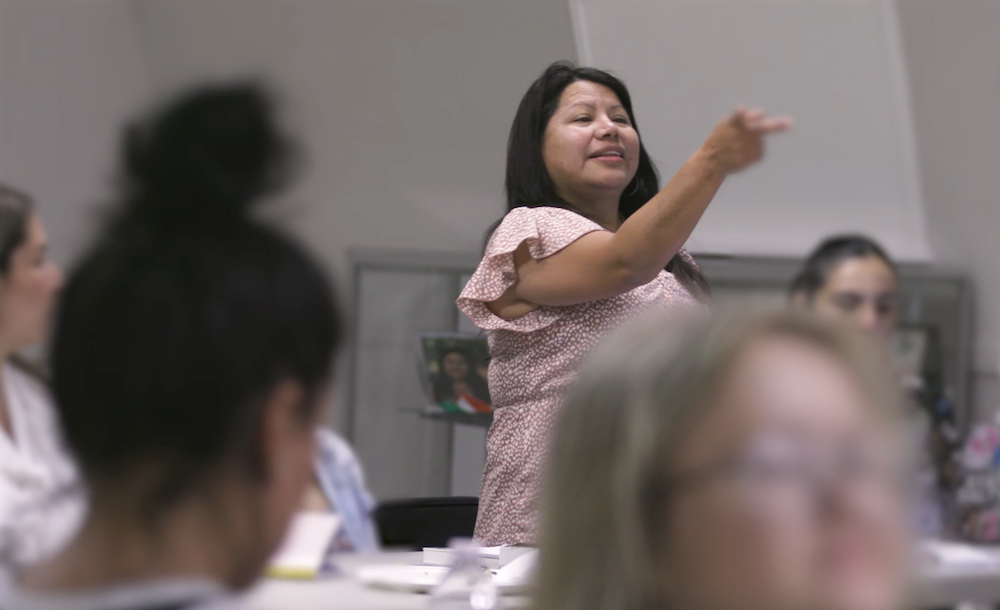

Maricela Sanchez, an investigator with the ACLU Foundation of Northern California, has lived her whole life advocating for our liberties and investigating civil rights abuses in the Central Valley. But on the morning of Operation Return to Sender, her social media feed showed something she’d never seen before: Border Patrol vehicles cruising down Highway 99 in Bakersfield.

“I haven’t seen that happen ever,” she recalls.

Through the Kern County Rapid Response Network — a coalition with a hotline and volunteers trained to document enforcement actions — and other partners, Sanchez helped interview dozens of people caught in the raids. Border Patrol foricibly reached into someone’s pocket to grab their ID from them. Another woman was driving home from work when she was pulled over by unmarked agents who never identified themselves. The next day, she was across the border in Mexico, separated from everything she had built in Bakersfield.

The stories Sanchez heard stayed with her: “Whenever I think about that week, I just think about how scary it was, how terrorizing it was. Just how much it affected our community.”

For Sanchez, these stories weren’t just case notes. They were the lives of her neighbors and friends. “So many children just stopped showing up to school. A lot of people didn’t feel comfortable coming to work. Folks completely stopped going to the store. How could that not impact you as a community member? Everyone should be concerned about this.”

“They thought no one would push back. But we did — and we’re not going anywhere.”

In Bakersfield, Rosa Lopez had been preparing for something like this for years. As a senior policy advocate with the ACLU Foundation of Southern California, she’d helped build the Kern County Rapid Response Network during the first Trump administration.

When the first calls came in on January 7, Lopez didn’t hesitate. She and her team dispatched volunteers across the county to record what they saw: license plates, uniforms, the way stops were conducted. Reports came in of canines, weapons drawn, and officers breaking windows — a level of aggression she’d never seen before.

This raid wasn’t routine. Border Patrol had set up a tent office, busing people straight to the border without legal access. Later, Lopez learned the raid had never been approved by the Department of Homeland Security. It was a rogue operation carried out by agents who thought they could act with impunity.

But the community was ready. Years of organizing meant people knew their rights, had red “Know Your Rights” cards in their pockets, and were willing to speak out. Lopez watched neighbors and community members step forward not just to report what they’d seen, but to stand beside those targeted, offering food, rides, and moral support.

“This is a moment that is going to test all of us,” Lopez said. “You can be afraid and hide, or you can be afraid and still stand up. We chose to stand up.”

The Stakes Beyond Kern County

The ACLU, United Farm Workers, and Bakersfield residents took Border Patrol to court for its unlawful and discriminatory actions during Operation Return to Sender. Agents operated far outside their legal jurisdiction, targeted people based on race, and denied them basic due process — all in violation of the Constitution. In April, in a major win for civil rights, a federal district court in California blocked the U.S. Border Patrol from using stop-and-arrest practices, which has led to zero warrantless arrest since the decision.

The ACLU and our partners will keep fighting in court and pushing for reforms that protect immigrant communities from racial profiling and abuse. We’ll also continue to work alongside residents, organizers, and labor groups to ensure no one has to live in fear of unlawful raids. We know this fight is about more than one county in California — it’s about defending the rights and dignity of people across the country.

Date

Thursday, August 28, 2025 - 6:15pmFeatured image