A Vision for Safe and Supportive Schools in California

Over the past few decades, police have become a dominant fixture in California schools. Their presence has devastating and discriminatory impacts on tens of thousands of California students.

Policing in the U.S. has historical roots in slave patrols, which violently abducted Black people who escaped enslavement, and in the forced dislocation of indigenous youth to “boarding schools” designed to erase their cultural ties. As communities across the country came together to reevaluate the role of police in enacting racism in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by police officers, youth activists effectively continued to advocate to remove police from schools. Since then, school districts in Oakland, Los Angeles, Pomona, and Claremont, among others, have fully eliminated or made progress towards eliminating school police.

“No Police in Schools: A Vision for Safe and Supportive Schools in CA” analyzes data from the U.S. Department of Education’s 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC), the 2019 California Racial and Identity Profiling Act (RIPA) Stops dataset, and data from Stockton Unified School District on police in schools. The data conclusively show harmful and discriminatory policing patterns in schools. School police contribute to the criminalization of tens of thousands of California students, resulting in them being pushed out of school and into the school-to-prison pipeline. Critically, the data suggest that schools underreport the number of assigned law enforcement officers, so these problems are likely even more severe.

KEY FINDINGS

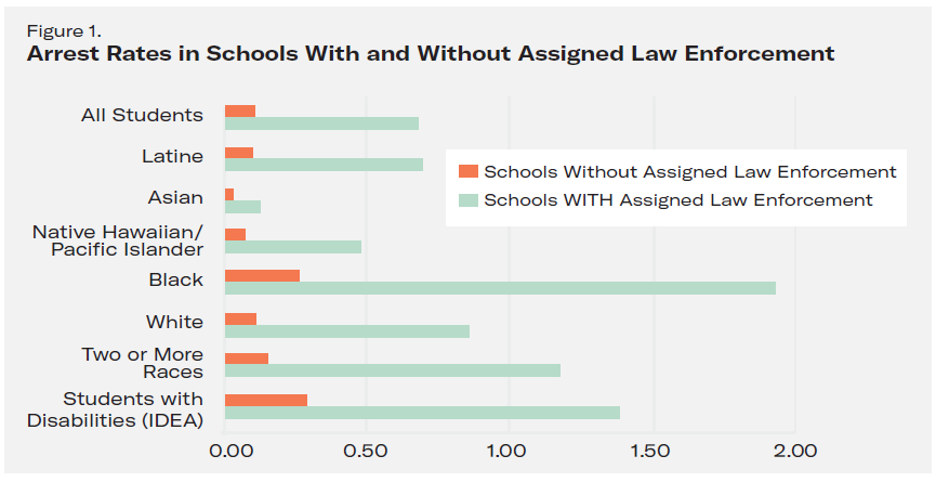

Students were far more vulnerable to arrest and referrals to police in schools with assigned law enforcement than in schools without.

- Black students’ arrest rates are 7.4 times higher in schools with assigned law enforcement than in schools without, and their law enforcement referral rates are 4.7 times higher.

- Latine students’ arrest rates are 6.9 times higher in schools with assigned law enforcement than in schools without, and their law enforcement referral rates are 4.4 times higher.

- Students with disabilities’ arrest rates are 4.6 times higher in schools with assigned law enforcement than in schools without, and their law enforcement referral rates are 4.8 times higher.

Law enforcement proponents attempt to explain the correlation between police in schools and heightened rates of arrests and referrals by speciously arguing that schools with assigned permanent law enforcement officers are inherently more dangerous. Baldwin Park Unified School District serves as an instructive counterexample to this assertion. From 2010 to 2017, the district had no police on staff. It then hired six officers in September 2017 and increased the police force to nine officers in 2019. Law enforcement referrals more than doubled to 347 in the 2017-18 CRDC after the district hired the police officers. Critically, during that time, arrests actually fell from 70 to 52, suggesting that the officers were called for issues that did not warrant arrests and should have been handled by school staff.

School police disproportionately arrest and cite Black students, Latine boys, and students with disabilities.

- Black students are three times more likely to be referred to law enforcement compared to white students.

- Black girls are six percent of California’s female student population but 18 percent of female student arrests.

- Latine boys are 28 percent of California’s students but 44 percent of student arrests.

- Students with disabilities are 11 percent of California’s students but 26 percent of student arrets.

- Black and Latine boys with disabilities are five percent of California’s students but 13 percent of referrals to law enforcement and 15 percent of school arrests.

The 2019 RIPA data confirm that police disproportionately stop Black students and subject them to harsher consequences.

- Black students are only 7.6 percent of students in schools in the dataset but represent 26 percent of law enforcement stops of students aged 5 to 19 by California’s 15 largest police agencies.

- Police handcuffed 15.7 percent of all students stopped in response to calls for service and 27.1 percent of all Black students stopped in response to calls for service.

- Police arrested only 12 percent of white students but 20 percent of Black students during stops.

A detailed analysis of policing in Stockton Unified School District also confirms the trends seen in the statewide data.

- From 2017 to 2020, Native American students were booked or cited by Stockton USD police at five times their rate of enrollment in school, and Black students were booked or cited at nearly three times their rate of enrollment.

- In 2019, Black students were six-and-a-half times more likely than white students to be booked or cited by Stockton USD police, and Native American students were over three times more likely than white students to be booked or cited by Stockton USD police.

“I want the removal of police from schools, starting IMMEDIATELY with elementary and middle schools. There is no situation that should require constant or even regular police presence with children so young. Please do not make the mistake of being yet another system that has taught children of color that they do not matter.” – Current Los Angeles USD Student

RECOMMENDATION

No school in California should have a permanent police officer. School districts should not be able to create their own police departments or reserve forces, nor should they coordinate with any outside law enforcement agency to station law enforcement on a school campus.

To achieve justice for our youth and to provide them with the education they deserve, we must reevaluate the entire system: reimagining safety without police and school hardening measures, reinvesting in the positive supports that actually help our students, and fundamentally changing the culture of our schools.

RESOURCES

Related Issues

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.