This statement was delivered in front of the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship for a hearing on the impact of current immigration policies on service members and veterans, and their families.

For more than 200 years, Congress has promised immigrant recruits expedited citizenship in exchange for military service: if you are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for this country, we will honor your sacrifices with citizenship.

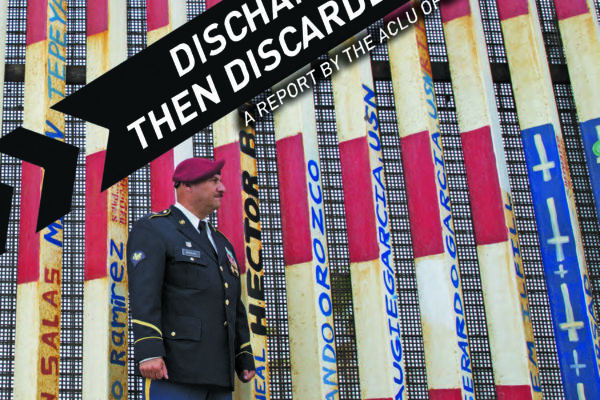

But since 1996, the United States has betrayed that promise. We have instead deported thousands of our veterans.

Every day we deport more. Just two weeks ago, ICE deported Jose Segovia Benitez, a two-time Iraq war combat veteran who suffered a traumatic brain injury, and who, like many, struggles with PTSD and substance abuse. Jose came to the U.S. as a 3-year-old child, he knows no other home than the U.S. Now he fears for his life in El Salvador.

These deportations are unconscionable and immoral. They are the result of three forces working together:

- The punishing and unforgiving 1996 laws that created lifetime bars to naturalization and mandatory deportation;

- The failure of the U.S. government to naturalize noncitizen service members while they are serving; and

- Hyper-aggressive immigration enforcement over the past decade.

Deported veterans are nearly all former Lawful Permanent Residents (or green card holders). Of those we interviewed for our report, half served during periods of war. And most came to the U.S. under the age of 10 — meaning the United States is the only country they know as home.

Changes made to our immigration laws in 1996 were so excessively punitive that certain criminal convictions, even convictions such as writing a bad check or possession for sale of marijuana, even convictions for which a person may serve no time in jail at all, require deportation and bar naturalization for life.

The '96 laws dramatically expanded the definition of the category of deportable offenses known as "aggravated felonies." Today, the term encompasses a whole host of nonviolent misdemeanors that are neither aggravated nor felonies.

And the law made deportation mandatory for any LPR with an aggravated felony by eliminating all forms of judicial discretion.

Meaning, a single criminal conviction, one mistake, can equal a lifetime of banishment. No exceptions.

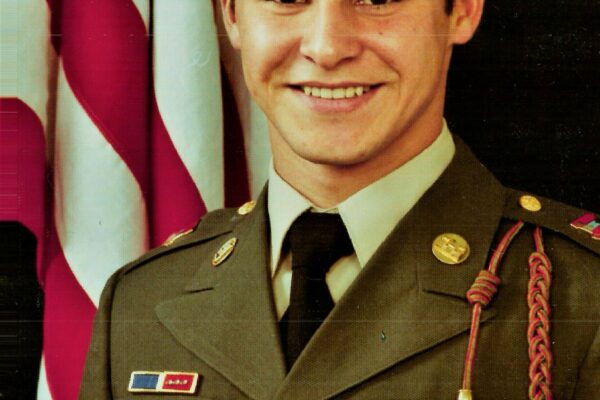

It means that when Mario Martinez goes before an immigration judge in March, the judge will not be permitted to consider whether deportation for a domestic violence conviction that occurred more than 10 years ago is a fair outcome. The judge will not be able to consider whether it's a fair outcome for a man who served honorably in the Army for six years, earning the rank of Sergeant; who has lived in the U.S. for 52 years, since he was only 4 years old; who has a successful engineering career, two grown sons, a granddaughter, and an extended family who are all U.S. citizens. The judge will not be able to consider that deportation means forcing him to live the remainder of his life estranged from everything he knows and loves.

Because the law says one mistake and you're out.

Take action now to change Mario's fate.

Citizen and noncitizen veterans equally struggle with reentry into civilian life following discharge. Substance abuse, mental health issues, and anger can lead to contact with the criminal justice system. As a society, we look to rehabilitative solutions to address the scars of war and trauma that inflict our veterans. But our immigration policy looks the other way.

Jorge Salcedo was deported for the crime of spitting on a police officer, which the law at the time defined as an aggravated felony. He paid for that crime and served one year in Connecticut prison. But at the conclusion of his sentence, ICE was at the prison door. ICE arrested him and detained him for 3 ½ years without the right to bail, while it pursued his deportation. And then it deported him. It did not matter that he served eight honorable years in the Army. It did not matter that deportation denied his daughters their father during their critical years of childhood.

One mistake.

Jorge sits here today because a change in law allowed him to get his green card back. He is one of the lucky few — most deported veterans have no such avenues for return.

The U.S. would not be deporting its veterans had the government kept its promise and made them citizens when they were serving in the military.

But over the years, numerous obstacles have stood in the way of service members naturalizing. None are greater than the obstacles service members face today.

Department of Defense policies intentionally block current service members' ability to obtain citizenship through military service. And USCIS sits on military naturalization applications and simply refuses to move them forward. These actions are unlawful and violate 200 years of Congressional directives.

The repatriated and naturalized veterans in this chamber today — Hector, Jorge, Miguel Perez and Yea Ji Sea, sitting behind me — embody the hope of deported veterans around the world that one day too they will get a chance to come home. Their hopes lay at the feet of Congress. They did not turn their backs on our country in its time of need; we must not turn our backs on them.

Urge Governor Newsom to pardon Mario Martinez.

Watch the full congressional hearing, including testimony from Hector Barajas, a repatriated veteran and Director and Founder of Deported Veterans Support House, and Margaret Stock, immigration attorney and Lieutenant Colonel (Retired), Military Police Corps, US Army Reserve.

Read the written testimony of Jennie Pasquarella, Director of Immigrants' Rights and Senior Staff Attorney, submitted to the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship.